Maximum a posteriori estimation

In Bayesian statistics, a maximum a posteriori probability (MAP) estimate is a mode of the posterior distribution. The MAP can be used to obtain a point estimate of an unobserved quantity on the basis of empirical data. It is closely related to Fisher's method of maximum likelihood (ML), but employs an augmented optimization objective which incorporates a prior distribution over the quantity one wants to estimate. MAP estimation can therefore be seen as a regularization of ML estimation.

Contents |

Description

Assume that we want to estimate an unobserved population parameter  on the basis of observations

on the basis of observations  . Let

. Let  be the sampling distribution of

be the sampling distribution of  , so that

, so that  is the probability of

is the probability of  when the underlying population parameter is

when the underlying population parameter is  . Then the function

. Then the function

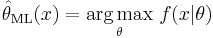

is known as the likelihood function and the estimate

is the maximum likelihood estimate of  .

.

Now assume that a prior distribution  over

over  exists. This allows us to treat

exists. This allows us to treat  as a random variable as in Bayesian statistics. Then the posterior distribution of

as a random variable as in Bayesian statistics. Then the posterior distribution of  is as follows:

is as follows:

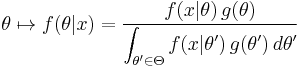

where  is density function of

is density function of  ,

,  is the domain of

is the domain of  . This is a straightforward application of Bayes' theorem.

. This is a straightforward application of Bayes' theorem.

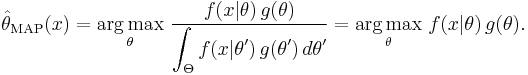

The method of maximum a posteriori estimation then estimates  as the mode of the posterior distribution of this random variable:

as the mode of the posterior distribution of this random variable:

The denominator of the posterior distribution (so-called partition function) does not depend on  and therefore plays no role in the optimization. Observe that the MAP estimate of

and therefore plays no role in the optimization. Observe that the MAP estimate of  coincides with the ML estimate when the prior

coincides with the ML estimate when the prior  is uniform (that is, a constant function). The MAP estimate is a limit of Bayes estimators under a sequence of 0-1 loss functions, but generally not a Bayes estimator per se, unless

is uniform (that is, a constant function). The MAP estimate is a limit of Bayes estimators under a sequence of 0-1 loss functions, but generally not a Bayes estimator per se, unless  is discrete.

is discrete.

Computing

MAP estimates can be computed in several ways:

- Analytically, when the mode(s) of the posterior distribution can be given in closed form. This is the case when conjugate priors are used.

- Via numerical optimization such as the conjugate gradient method or Newton's method. This usually requires first or second derivatives, which have to be evaluated analytically or numerically.

- Via a modification of an expectation-maximization algorithm. This does not require derivatives of the posterior density.

- Via a Monte Carlo method using simulated annealing

Criticism

While MAP estimation is a limit of Bayes estimators (under the 0-1 loss function), it is not very representative of Bayesian methods in general. This is because MAP estimates are point estimates, whereas Bayesian methods are characterized by the use of distributions to summarize data and draw inferences: thus, Bayesian methods tend to report the posterior mean or median instead, together with credible intervals. This is both because these estimators are optimal under squared-error and linear-error loss respectively - which are more representative of typical loss functions - and because the posterior distribution may not have a simple analytic form: in this case, the distribution can be simulated using Markov chain Monte Carlo techniques, while optimization to find its mode(s) may be difficult or impossible.

In many types of models, such as mixture models, the posterior may be multi-modal. In such a case, the usual recommendation is that one should choose the highest mode: this is not always feasible (global optimization is a difficult problem), nor in some cases even possible (such as when identifiability issues arise). Furthermore, the highest mode may be uncharacteristic of the majority of the posterior.

Finally, unlike ML estimators, the MAP estimate is not invariant under reparameterization. Switching from one parameterization to another involves introducing a Jacobian that impacts on the location of the maximum.

As an example of the difference between Bayes estimators mentioned above (mean and median estimators) and using an MAP estimate, consider the case where there is a need to classify inputs  as either positive or negative (for example, loans as risky or safe). Suppose there are just three possible hypotheses about the correct method of classification

as either positive or negative (for example, loans as risky or safe). Suppose there are just three possible hypotheses about the correct method of classification  ,

,  and

and  with posteriors 0.4, 0.3 and 0.3 respectively. Suppose given a new instance,

with posteriors 0.4, 0.3 and 0.3 respectively. Suppose given a new instance,  ,

,  classifies it as positive, whereas the other two classify it as negative. Using the MAP estimate for the correct classifier

classifies it as positive, whereas the other two classify it as negative. Using the MAP estimate for the correct classifier  ,

,  is classified as positive, whereas the Bayes estimators would average over all hypotheses and classify

is classified as positive, whereas the Bayes estimators would average over all hypotheses and classify  as negative.

as negative.

Example

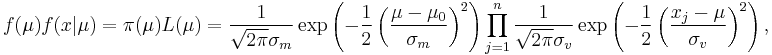

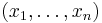

Suppose that we are given a sequence  of IID

of IID  random variables and an a priori distribution of

random variables and an a priori distribution of  is given by

is given by  . We wish to find the MAP estimate of

. We wish to find the MAP estimate of  .

.

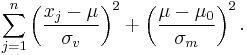

The function to be maximized is then given by

which is equivalent to minimizing the following function of  :

:

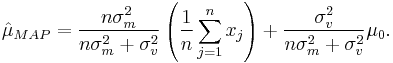

Thus, we see that the MAP estimator for μ is given by

which turns out to be a linear interpolation between the prior mean and the sample mean weighted by their respective covariances.

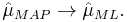

The case of  is called a non-informative prior and leads to an ill-defined a priori probability distribution; in this case

is called a non-informative prior and leads to an ill-defined a priori probability distribution; in this case

References

- M. DeGroot, Optimal Statistical Decisions, McGraw-Hill, (1970).

- Harold W. Sorenson, (1980) "Parameter Estimation: Principles and Problems", Marcel Dekker.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||